That is the tension many large PMCs are living in right now.

Most, run on complex tech stacks.

- A screening vendor for reports.

- A fraud layer for identity and document checks.

- A PMS for everything operational.

- Sometimes a BI tool on top.

- And now AI is making its way into decisions and exceptions.

These tools do a lot of work.

And most of them do that work correctly.

Yet decisions still fail when they are challenged. Not because the tool malfunctioned. Because the workflow around the tool left gaps — gaps that become liabilities the moment someone asks a simple question:

“Show me how you reached this decision.”

That is where most operators discover the truth:

Tools help. Workflows defend.

Not because the tools failed.

Because the workflow did.

Remember, the stack is not your safeguard

Across federal reports and enforcement actions, the pattern is consistent.

Tools improve speed, scale, and consistency.

But the responsibility for how information is used stays with the housing provider.

Regulators expect you to know:

- what criteria you use

- how those criteria are applied

- when exceptions are allowed

- how you document the decision

- how you handle disputes

- how you prove compliance six months later

This is where many leaders underestimate their risk. They assume that because the tools are reputable, the decisions are defensible.

But defensibility is rarely tested inside the tool. It is tested in the workflow that surrounds it.

None of that is news to most executives. We already know tools are not perfect.

The more practical problem to consider is this:

You can swap vendors, add another fraud layer, or renegotiate SLAs but if the way your team uses those tools is loose, undocumented, or inconsistent, your risk profile does not really change.

Where workflows actually break in practice

Even well-run portfolios have soft spots in their process.

These weak points rarely show up day to day. They appear only when something goes wrong — a dispute, a complaint, a regulator inquiry, or a plaintiff attorney asking for the full packet.

- Mismatched or misidentified records

Wrong person, similar name, shared address, or merged files. CFPB has called out “shoddy name-matching procedures” as a specific source of harm in background screening. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau - Outdated or sealed information still in play

Expunged, sealed, or too old records that continue to appear in reports and drive decisions, even when state law or policy says they should not. HUD Fair Housing Guidance - Missing outcomes and context

Arrests with no disposition, civil cases without a final status, or debts shown without showing resolution. These are exactly the kinds of gaps CFPB and advocacy groups flag as misleading in tenant reports. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau+2NCLC+2 - Limited or confusing dispute paths

FTC and CFPB keep reminding tenants that they can and should dispute errors. That only matters if your internal workflow knows what to do when a dispute hits your desk, not just the CRA’s. Consumer Advice+2National Low Income Housing Coalition+2

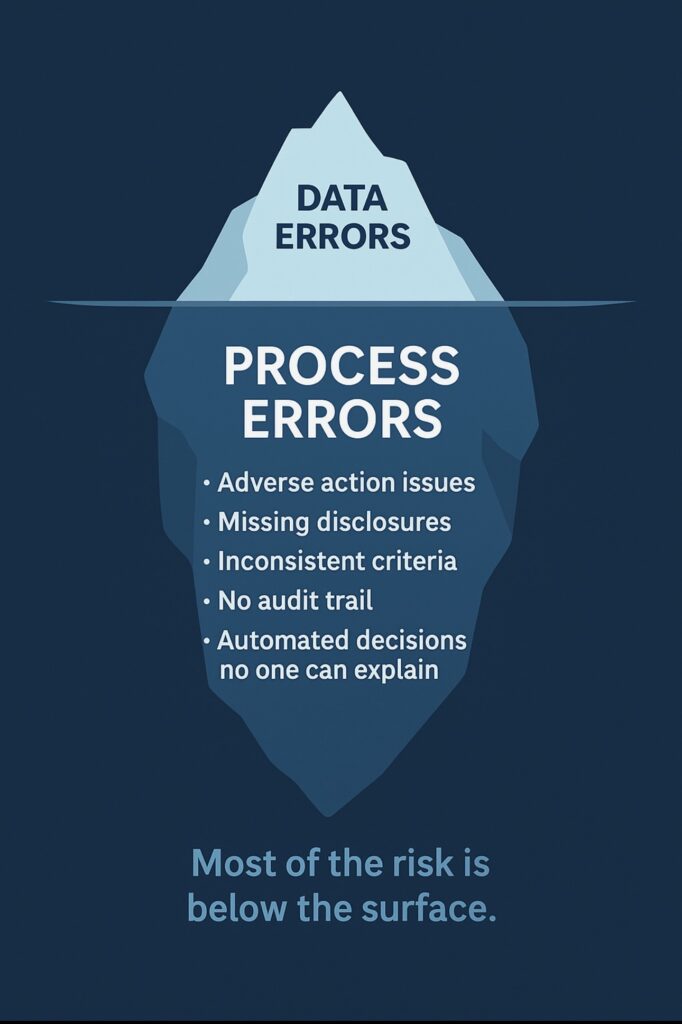

Notice something important here.

Most of these issues are not about a single “bad” tool.

They are about how information flows across tools, how people interpret it, and how exceptions are handled.

That is workflow.

3. The real liability: over reliance on “good” tools

From a risk point of view, over reliance on tools shows up in a few specific ways inside a large PMC.

a) “The vendor has us covered”

The assumption sounds reasonable:

Our screening partner is the CRA. They handle accuracy.

We just consume the decision or recommendation.

Regulators do not see it that way.

FCRA places duties on users of reports, not only on the companies that produce them. HUD’s fair housing guidance treats the housing provider as responsible for how criteria are chosen, how they are applied, and how applicants can challenge them, even when a third party system is doing the heavy lifting. Federal Trade Commission+2Navigate Housing+2

If your internal workflow is “click accept, move on” you may be outsourcing data collection, but you are not outsourcing liability.

b) Configuration by folklore

Many portfolios have screening criteria that evolved over time:

- A regional manager asked for “stricter settings” after a bad loss.

- Legal asked for language to be added to a notice template.

- A site tweaked income thresholds based on “what works in this market”.

Those changes may be defensible in context.

The risk is when criteria live inside a tool configuration only, without a clean, current, and accessible policy that explains:

- what the rule is

- why it exists

- how it should be applied

- how exceptions are handled

When a dispute or HUD inquiry shows up, you need the workflow story, not just a screenshot of vendor settings.

c) Exceptions in email, decisions in the dark

This is one of the most common patterns operators describe privately:

- Leasing agent emails a supervisor for an exception.

- Supervisor replies “approved, but watch for X next time”.

- PMS note: “approved by manager”.

That decision may have been reasonable.

What you do not have is a packet that shows:

- what the original data said

- what rule would have done by default

- why an exception was granted

- who approved it and when

If the only evidence is a line in a PMS note and a buried email thread, the workflow is functionally invisible.

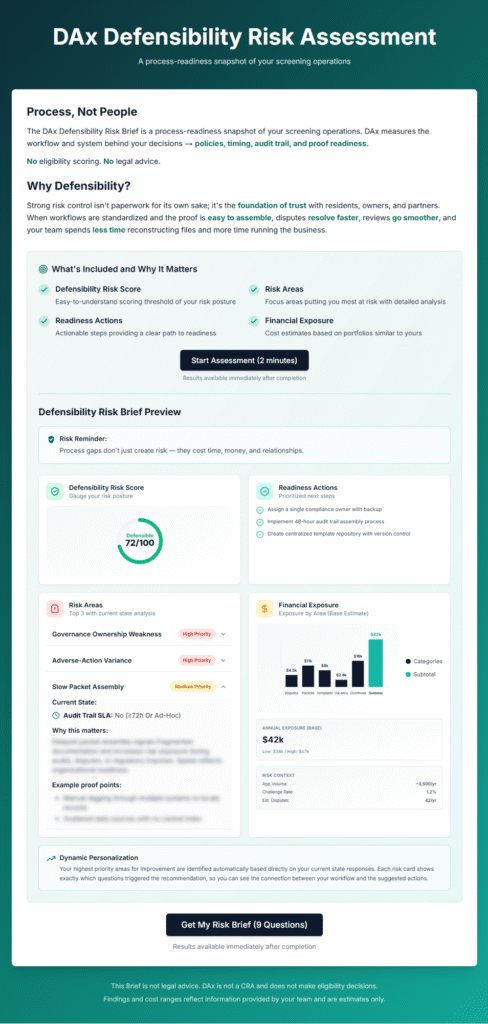

4. What “your workflow cannot be wrong” actually means

No workflow will be perfect.

No system can remove all risk.

“Cannot be wrong” here is not about never making a tough call.

It is about building a process that is:

- Consistent

The same inputs lead to the same path, across properties and teams, unless a documented exception applies. - Transparent

You can show, in a packet, what criteria were in effect, what data was used, and how you moved from data to decision. - Controllable

You can update criteria, adjust rules, or add a new tool in a way that is versioned, reviewed, and traceable. - Contestable

When someone challenges a decision, you have a defined path to review the data, re run the logic if needed, and respond in a way that lines up with FCRA and fair housing expectations.

In other words, workflows that are built to be defended, not rebuilt after something goes wrong.

5. From tools first to workflow first

For a large PMC, a workflow first posture usually starts with a few simple but hard questions:

- If a regulator, plaintiff attorney, or fair housing group asked for the full story on a denied application, what would we hand them today?

A clean packet, or a scramble across email, PMS, and vendor portals. - Where, in our process, are we depending on “the system” to do something we have never actually documented as policy?

Auto declines, automated notices, templated criteria inside a vendor dashboard. - When disputes, complaints, or “please review this decision” requests show up, do we have one standard workflow or ten different local versions?

From there, the tools become components in a broader defensibility design:

- Screening vendor for data and risk factors

- PMS for core record and notes

- Document or fraud layer for additional verification

- Internal workflow for criteria, exceptions, and packet assembly

Every tool can be right inside its own box.

Your defensibility lives in how those boxes connect, how people use them, and what you can prove after the fact.

Closing thought

The market has spent a decade buying better tools.

Regulators are now asking better questions.

For executives, the real strategic shift is simple:

Stop asking “is this tool accurate enough”.

Start asking “if this decision were challenged six months from now, could we explain what happened, why it was reasonable, and how we would catch it if the tool got it wrong”.

Every tool can be right.

Your workflow cannot be wrong.

That is where defensibility lives.